1. Overview

The SOLID design principles were introduced by Robert C. Martin in his 2000 paper, Design Principles and Design Patterns. SOLID design principles help us create more maintainable, understandable, and flexible software.

In this article, we’ll discuss the Liskov Substitution Principle, which is the “L” in the acronym.

2. The Open/Closed Principle

To understand the Liskov Substitution Principle, we must first understand the Open/Closed Principle (the “O” from SOLID).

The goal of the Open/Closed principle encourages us to design our software so we add new features only by adding new code. When this is possible, we have loosely coupled, and thus easily maintainable applications.

3. An Example Use Case

Let’s look at a Banking Application example to understand the Open/Closed Principle some more.

3.1. Without the Open/Closed Principle

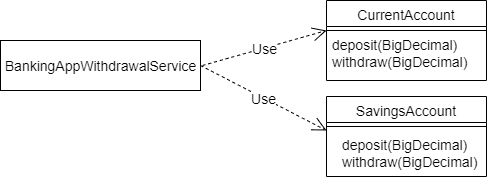

Our banking application supports two account types – “current” and “savings”. These are represented by the classes CurrentAccount and SavingsAccount respectively.

The BankingAppWithdrawalService serves the withdrawal functionality to its users:

Unfortunately, there is a problem with extending this design. The BankingAppWithdrawalService is aware of the two concrete implementations of account*.* Therefore, the BankingAppWithdrawalService would need to be changed every time a new account type is introduced.

3.2. Using the Open/Closed Principle to Make the Code Extensible

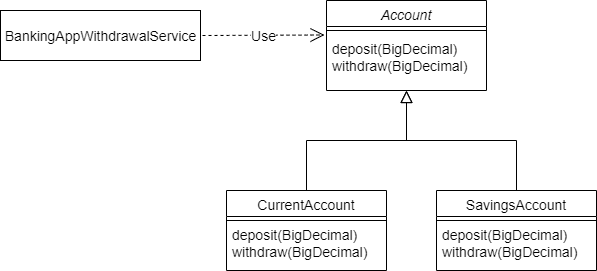

Let’s redesign the solution to comply with the Open/Closed principle. We’ll close BankingAppWithdrawalService from modification when new account types are needed, by using an Account base class instead:

Here, we introduced a new abstract Account class that CurrentAccount and SavingsAccount extend.

The BankingAppWithdrawalService no longer depends on concrete account classes. Because it now depends only on the abstract class, it need not be changed when a new account type is introduced.

Consequently, the BankingAppWithdrawalService is open for the extension with new account types, but closed for modification, in that the new types don’t require it to change in order to integrate.

3.3. Java Code

Let’s look at this example in Java. To begin with, let’s define the Account class:

public abstract class Account {

protected abstract void deposit(BigDecimal amount);

/**

* Reduces the balance of the account by the specified amount

* provided given amount > 0 and account meets minimum available

* balance criteria.

*

* @param amount

*/

protected abstract void withdraw(BigDecimal amount);

}

And, let’s define the BankingAppWithdrawalService:

public class BankingAppWithdrawalService {

private Account account;

public BankingAppWithdrawalService(Account account) {

this.account = account;

}

public void withdraw(BigDecimal amount) {

account.withdraw(amount);

}

}

Now, let’s look at how, in this design, a new account type might violate the Liskov Substitution Principle.

3.4. A New Account Type

The bank now wants to offer a high interest-earning fixed-term deposit account to its customers.

To support this, let’s introduce a new FixedTermDepositAccount class. A fixed-term deposit account in the real world “is a” type of account. This implies inheritance in our object-oriented design.

So, let’s make FixedTermDepositAccount a subclass of Account:

public class FixedTermDepositAccount extends Account {

// Overridden methods...

}

So far, so good. However, the bank doesn’t want to allow withdrawals for the fixed-term deposit accounts.

This means that the new FixedTermDepositAccount class can’t meaningfully provide the withdraw method that Account defines. One common workaround for this is to make FixedTermDepositAccount throw an UnsupportedOperationException in the method it cannot fulfill:

public class FixedTermDepositAccount extends Account {

@Override

protected void deposit(BigDecimal amount) {

// Deposit into this account

}

@Override

protected void withdraw(BigDecimal amount) {

throw new UnsupportedOperationException("Withdrawals are not supported by FixedTermDepositAccount!!");

}

}

3.5. Testing Using the New Account Type

While the new class works fine, let’s try to use it with the BankingAppWithdrawalService:

Account myFixedTermDepositAccount = new FixedTermDepositAccount();

myFixedTermDepositAccount.deposit(new BigDecimal(1000.00));

BankingAppWithdrawalService withdrawalService = new BankingAppWithdrawalService(myFixedTermDepositAccount);

withdrawalService.withdraw(new BigDecimal(100.00));

Unsurprisingly, the banking application crashes with the error:

Withdrawals are not supported by FixedTermDepositAccount!!

There’s clearly something wrong with this design if a valid combination of objects results in an error.

3.6. What Went Wrong?

The BankingAppWithdrawalService is a client of the Account class. It expects that both Account and its subtypes guarantee the behavior that the Account class has specified for its withdraw method:

/**

* Reduces the account balance by the specified amount

* provided given amount > 0 and account meets minimum available

* balance criteria.

*

* @param amount

*/

protected abstract void withdraw(BigDecimal amount);

However, by not supporting the withdraw method, the FixedTermDepositAccount violates this method specification*.* Therefore, we cannot reliably substitute FixedTermDepositAccount for Account.

In other words, the FixedTermDepositAccount has violated the Liskov Substitution Principle.

3.7. Can’t We Handle the Error in BankingAppWithdrawalService?

We could amend the design so that the client of Account‘s withdraw method has to be aware of a possible error in calling it. However, this would mean that clients have to have special knowledge of unexpected subtype behavior. This starts to break the Open/Closed principle.

In other words, for the Open/Closed Principle to work well, all subtypes must be substitutable for their supertype without ever having to modify the client code. Adhering to the Liskov Substitution Principle ensures this substitutability.

Let’s now look at the Liskov Substitution Principle in detail.

4. The Liskov Substitution Principle

4.1. Definition

Robert C. Martin summarizes it:

Subtypes must be substitutable for their base types.

Barbara Liskov, defining it in 1988, provided a more mathematical definition:

If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T.

Let’s understand these definitions a bit more.

4.2. When Is a Subtype Substitutable for Its Supertype?

A subtype doesn’t automatically become substitutable for its supertype. To be substitutable, the subtype must behave like its supertype.

An object’s behavior is the contract that its clients can rely on. The behavior is specified by the public methods, any constraints placed on their inputs, any state changes that the object goes through, and the side effects from the execution of methods.

Subtyping in Java requires the base class’s properties and methods are available in the subclass.

However, behavioral subtyping means that not only does a subtype provide all of the methods in the supertype, but it must adhere to the behavioral specification of the supertype. This ensures that any assumptions made by the clients about the supertype behavior are met by the subtype.

This is the additional constraint that the Liskov Substitution Principle brings to object-oriented design.

Let’s now refactor our banking application to address the problems we encountered earlier.

5. Refactoring

To fix the problems we found in the banking example, let’s start by understanding the root cause.

5.1. The Root Cause

In the example, our FixedTermDepositAccount was not a behavioral subtype of Account.

The design of Account incorrectly assumed that all Account types allow withdrawals. Consequently, all subtypes of Account, including FixedTermDepositAccount which doesn’t support withdrawals, inherited the withdraw method.

Though we could work around this by extending the contract of Account, there are alternative solutions.

5.2. Revised Class Diagram

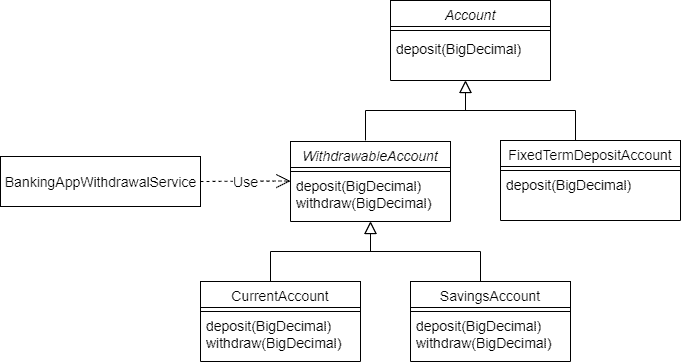

Let’s design our account hierarchy differently:

Because all accounts do not support withdrawals, we moved the withdraw method from the Account class to a new abstract subclass WithdrawableAccount. Both CurrentAccount and SavingsAccount allow withdrawals. So they’ve now been made subclasses of the new WithdrawableAccount.

This means BankingAppWithdrawalService can trust the right type of account to provide the withdraw function.

5.3. Refactored BankingAppWithdrawalService

BankingAppWithdrawalService now needs to use the WithdrawableAccount*:*

public class BankingAppWithdrawalService {

private WithdrawableAccount withdrawableAccount;

public BankingAppWithdrawalService(WithdrawableAccount withdrawableAccount) {

this.withdrawableAccount = withdrawableAccount;

}

public void withdraw(BigDecimal amount) {

withdrawableAccount.withdraw(amount);

}

}

As for FixedTermDepositAccount, we retain Account as its parent class. Consequently, it inherits only the deposit behavior that it can reliably fulfill and no longer inherits the withdraw method that it doesn’t want. This new design avoids the issues we saw earlier.

6. Rules

Let’s now look at some rules/techniques concerning method signatures, invariants, preconditions, and postconditions that we can follow and use to ensure we create well-behaved subtypes.

In their book Program Development in Java: Abstraction, Specification, and Object-Oriented Design, Barbara Liskov and John Guttag grouped these rules into three categories – the signature rule, the properties rule, and the methods rule.

Some of these practices are already enforced by Java’s overriding rules.

We should note some terminology here. A wide type is more general – Object for instance could mean ANY Java object and is wider than, say, CharSequence, where String is very specific and therefore narrower.

6.1. Signature Rule – Method Argument Types

This rule states that the overridden subtype method argument types can be identical or wider than the supertype method argument types.

Java’s method overriding rules support this rule by enforcing that the overridden method argument types match exactly with the supertype method.

6.2. Signature Rule – Return Types

The return type of the overridden subtype method can be narrower than the return type of the supertype method. This is called covariance of the return types. Covariance indicates when a subtype is accepted in place of a supertype. Java supports the covariance of return types. Let’s look at an example:

public abstract class Foo {

public abstract Number generateNumber();

// Other Methods

}

The generateNumber method in Foo has return type as Number. Let’s now override this method by returning a narrower type of Integer:

public class Bar extends Foo {

@Override

public Integer generateNumber() {

return new Integer(10);

}

// Other Methods

}

Because Integer IS-A Number, a client code that expects Number can replace Foo with Bar without any problems.

On the other hand, if the overridden method in Bar were to return a wider type than Number, e.g. Object, that might include any subtype of Object e.g. a Truck. Any client code that relied on the return type of Number could not handle a Truck!

Fortunately, Java’s method overriding rules prevent an override method returning a wider type.

6.3. Signature Rule – Exceptions

The subtype method can throw fewer or narrower (but not any additional or broader) exceptions than the supertype method.

This is understandable because when the client code substitutes a subtype, it can handle the method throwing fewer exceptions than the supertype method. However, if the subtype’s method throws new or broader checked exceptions, it would break the client code.

Java’s method overriding rules already enforce this rule for checked exceptions. However, overriding methods in Java CAN THROW any RuntimeException regardless of whether the overridden method declares the exception.

6.4. Properties Rule – Class Invariants

A class invariant is an assertion concerning object properties that must be true for all valid states of the object.

Let’s look at an example:

public abstract class Car {

protected int limit;

// invariant: speed < limit;

protected int speed;

// postcondition: speed < limit

protected abstract void accelerate();

// Other methods...

}

The Car class specifies a class invariant that speed must always be below the limit. The invariants rule states that all subtype methods (inherited and new) must maintain or strengthen the supertype’s class invariants.

Let’s define a subclass of Car that preserves the class invariant:

public class HybridCar extends Car {

// invariant: charge >= 0;

private int charge;

@Override

// postcondition: speed < limit

protected void accelerate() {

// Accelerate HybridCar ensuring speed < limit

}

// Other methods...

}

In this example, the invariant in Car is preserved by the overridden accelerate method in HybridCar. The HybridCar additionally defines its own class invariant charge >= 0, and this is perfectly fine.

Conversely, if the class invariant is not preserved by the subtype, it breaks any client code that relies on the supertype.

6.5. Properties Rule – History Constraint

The history constraint states that the subclass methods (inherited or new) shouldn’t allow state changes that the base class didn’t allow.

Let’s look at an example:

public abstract class Car {

// Allowed to be set once at the time of creation.

// Value can only increment thereafter.

// Value cannot be reset.

protected int mileage;

public Car(int mileage) {

this.mileage = mileage;

}

// Other properties and methods...

}

The Car class specifies a constraint on the mileage property. The mileage property can be set only once at the time of creation and cannot be reset thereafter.

Let’s now define a ToyCar that extends Car:

public class ToyCar extends Car {

public void reset() {

mileage = 0;

}

// Other properties and methods

}

The ToyCar has an extra method reset that resets the mileage property. In doing so, the ToyCar ignored the constraint imposed by its parent on the mileage property. This breaks any client code that relies on the constraint. So, ToyCar isn’t substitutable for Car.

Similarly, if the base class has an immutable property, the subclass should not permit this property to be modified. This is why immutable classes should be final.

6.6. Methods Rule – Preconditions

A precondition should be satisfied before a method can be executed. Let’s look at an example of a precondition concerning parameter values:

public class Foo {

// precondition: 0 < num <= 5

public void doStuff(int num) {

if (num <= 0 || num > 5) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Input out of range 1-5");

}

// some logic here...

}

}

Here, the precondition for the doStuff method states that the num parameter value must be between 1 and 5. We have enforced this precondition with a range check inside the method. A subtype can weaken (but not strengthen) the precondition for a method it overrides. When a subtype weakens the precondition, it relaxes the constraints imposed by the supertype method.

Let’s now override the doStuff method with a weakened precondition:

public class Bar extends Foo {

@Override

// precondition: 0 < num <= 10

public void doStuff(int num) {

if (num <= 0 || num > 10) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Input out of range 1-10");

}

// some logic here...

}

}

Here, the precondition is weakened in the overridden doStuff method to 0 < num <= 10, allowing a wider range of values for num. All values of num that are valid for Foo.doStuff are valid for Bar.doStuff as well. Consequently, a client of Foo.doStuff doesn’t notice a difference when it replaces Foo with Bar.

Conversely, when a subtype strengthens the precondition (e.g. 0 < num <= 3 in our example), it applies more stringent restrictions than the supertype. For example, values 4 & 5 for num are valid for Foo.doStuff, but are no longer valid for Bar.doStuff.

This would break the client code that does not expect this new tighter constraint.

6.7. Methods Rule – Postconditions

A postcondition is a condition that should be met after a method is executed.

Let’s look at an example:

public abstract class Car {

protected int speed;

// postcondition: speed must reduce

protected abstract void brake();

// Other methods...

}

Here, the brake method of Car specifies a postcondition that the Car‘s speed must reduce at the end of the method execution. The subtype can strengthen (but not weaken) the postcondition for a method it overrides. When a subtype strengthens the postcondition, it provides more than the supertype method.

Now, let’s define a derived class of Car that strengthens this precondition:

public class HybridCar extends Car {

// Some properties and other methods...

@Override

// postcondition: speed must reduce

// postcondition: charge must increase

protected void brake() {

// Apply HybridCar brake

}

}

The overridden brake method in HybridCar strengthens the postcondition by additionally ensuring that the charge is increased as well. Consequently, any client code relying on the postcondition of the brake method in the Car class notices no difference when it substitutes HybridCar for Car.

Conversely, if HybridCar were to weaken the postcondition of the overridden brake method, it would no longer guarantee that the speed would be reduced. This might break client code given a HybridCar as a substitute for Car.

7. Code Smells

How can we spot a subtype that is not substitutable for its supertype in the real world?

Let’s look at some common code smells that are signs of a violation of the Liskov Substitution Principle.

7.1. A Subtype Throws an Exception for a Behavior It Can’t Fulfill

We have seen an example of this in our banking application example earlier on.

Prior to the refactoring, the Account class had an extra method withdraw that its subclass FixedTermDepositAccount didn’t want. The FixedTermDepositAccount class worked around this by throwing the UnsupportedOperationException for the withdraw method. However, this was just a hack to cover up a weakness in the modeling of the inheritance hierarchy.

7.2. A Subtype Provides No Implementation for a Behavior It Can’t Fulfill

This is a variation of the above code smell. The subtype cannot fulfill a behavior and so it does nothing in the overridden method.

Here’s an example. Let’s define a FileSystem interface:

public interface FileSystem {

File[] listFiles(String path);

void deleteFile(String path) throws IOException;

}

Let’s define a ReadOnlyFileSystem that implements FileSystem:

public class ReadOnlyFileSystem implements FileSystem {

public File[] listFiles(String path) {

// code to list files

return new File[0];

}

public void deleteFile(String path) throws IOException {

// Do nothing.

// deleteFile operation is not supported on a read-only file system

}

}

Here, the ReadOnlyFileSystem doesn’t support the deleteFile operation and so doesn’t provide an implementation.

7.3. The Client Knows About Subtypes

If the client code needs to use instanceof or downcasting, then the chances are that both the Open/Closed Principle and the Liskov Substitution Principle have been violated.

Let’s illustrate this using a FilePurgingJob:

public class FilePurgingJob {

private FileSystem fileSystem;

public FilePurgingJob(FileSystem fileSystem) {

this.fileSystem = fileSystem;

}

public void purgeOldestFile(String path) {

if (!(fileSystem instanceof ReadOnlyFileSystem)) {

// code to detect oldest file

fileSystem.deleteFile(path);

}

}

}

Because the FileSystem model is fundamentally incompatible with read-only file systems, the ReadOnlyFileSystem inherits a deleteFile method it can’t support. This example code uses an instanceof check to do special work based on a subtype implementation.

7.4. A Subtype Method Always Returns the Same Value

This is a far more subtle violation than the others and is harder to spot. In this example, ToyCar always returns a fixed value for the remainingFuel property:

public class ToyCar extends Car {

@Override

protected int getRemainingFuel() {

return 0;

}

}

It depends on the interface, and what the value means, but generally hardcoding what should be a changeable state value of an object is a sign that the subclass is not fulfilling the whole of its supertype and is not truly substitutable for it.

8. Conclusion

In this article, we looked at the Liskov Substitution SOLID design principle.

The Liskov Substitution Principle helps us model good inheritance hierarchies. It helps us prevent model hierarchies that don’t conform to the Open/Closed principle.

Any inheritance model that adheres to the Liskov Substitution Principle will implicitly follow the Open/Closed principle.

To begin with, we looked at a use case that attempts to follow the Open/Closed principle but violates the Liskov Substitution Principle. Next, we looked at the definition of the Liskov Substitution Principle, the notion of behavioral subtyping, and the rules that subtypes must follow.

Finally, we looked at some common code smells that can help us detect violations in our existing code.

As always, the example code from this article is available over on GitHub.